Celso Simbine

Introduction

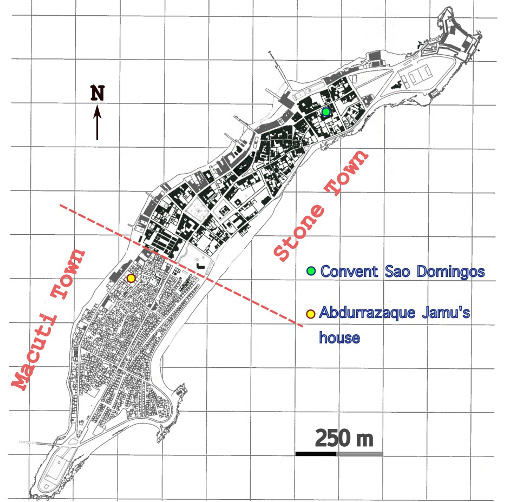

This work presents the results of an investigation of imported ceramics excavated on Mozambique Island, a part of East Africa that is sometimes overlooked. The ceramics that are described and analyzed in this work were recovered in 2019 by a team of archaeologists from the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at Eduardo Mondlane University. The excavations were carried out at two archaeological sites of Mozambique Island: Abdurrazaque Jamu house located in Macuti-town and Convent São Domingos located in Stone-town. Chinese and European ceramics constitute the largest types of material excavated from the sites and were useful in defining the relative chronology of the two archaeological contexts. These ceramics are frequently found in archaeological excavations across the eastern coast of Africa and have been associated with the intensification of Asian and European maritime trade that became a feature of the interconnected early modern world.

This study contributes to previous scholarship and archaeological understanding of this island’s role in the long-distance trade of Chinese and European ceramics around the Indian Ocean rim. The analysis of ceramics and the literature review provide additional clues to the cross-continental exchange between the seventeenth and early twentieth centuries CE, when the coast of Mozambique became an important center of transregional trade, particularly for the circulation of Chinese and European export-ware, including porcelain. Systematic archaeological research has shown that Chinese and European ceramics served fundamentally as exchange goods, since their diffusion on the coast and hinterland is mainly located at sites where commerce took place.

Location and Description of Mozambique Island

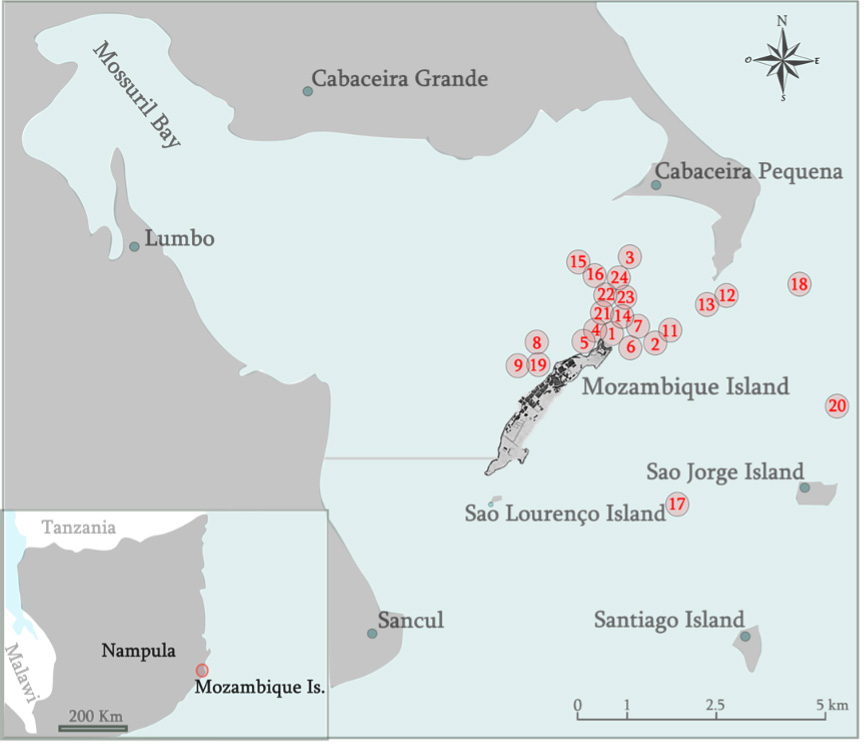

Mozambique Island is an archipelago with an extent of 445 square meters, surrounded by twenty-four submerged shipwrecks and composed of three uninhabited islands: Sāo Lourenço, São Jorge, and Santiago. It is situated in the northern region of the nation of Mozambique in Nampula province, on the coast of the Indian Ocean (fig. 1). Commercial exchange flourished between coastal Mozambicans and Arab merchants as early as the late first millennium CE, before the large-scale conversion of coastal east Africans to Islam (Duarte 1993). From the second millennium onwards Angoche district and Mozambique Island became centers of political and economic power (Mutiua 2014, 20). Thus, it is clear that before the arrival of the Portuguese, Mozambique Island was already a township inhabited by an Islamicized people and ruled by the hereditary leader, Sheikh Zacoeja, who controlled overseas and transcontinental exchange networks and had the authority to grant permission for foreign merchants to trade in the region (Lobato 1953, 11). Furthermore, in 1498, when Vasco Da Gama’s crew landed for the first time on Mozambique Island, they found a well-established political and economic system that facilitated commercial affairs and mediated relationships with those who arrived from other parts of the Indian Ocean rim (Newitt 2004, 23). Swahili and Arab communities deployed traditional maritime vessels, including zambucos, dhows, and pangaios, to navigate the Indian Ocean (Duarte 2012, 84).

Mozambique Island is about 3 km long and 500 m wide and is divided into two towns (fig. 2): on the north side of the island is located Stone-town, composed of stone-houses exhibiting different architectural styles that are often associated with Swahili and Arab cultures, but the most notable feature is the introduction of European architecture from circa 1570. These buildings are often connected directly to Portugal and particularly to the southern Algarve region (Monclaros 1975, 275). In the south of the island is located Macuti-town, which began to develop at a later time, starting in the 1800s. By contrast, it is composed of houses made of wattle and daub, and the roofs are made of macuti (palm leaves) laid on reed. The macuti houses are often associated with African traditional building styles, rather than overseas ones (Arkitektskolen I Aarhus 1985, 28).

Analysis of Imported Ceramics

I washed, labelled, and sorted the ceramics recovered from the excavations, according to units and layers. Then, I analyzed, typologically classified, counted, photographed with a scale, and finally placed them in plastic bags with respective fieldwork details recorded (Simbine 2021, 22). The finds were analyzed to determine the chronology, shape, and decorative pattern of each specimen (see Maguire 2007, 4). Furthermore, the analysis allowed typological classification and comparison with ceramics that may have been produced in regions abroad (see for example Klose 1997). It is important to note that the local chronological sequence and the study of exchange networks between Mozambique Island and neighboring communities during the early modern period were done by a team of archaeologists, including Duarte and Menezes (1996), Madiquida and Miguel (2004) and Simbine (2020; 2021). This essay draws on and further elucidates those findings.

Of the 258 total sherds of imported ceramics recovered in both sites, 78 sherds were recovered at Abdurrazaque Juma‘s house, which was a macuti-style structure. 26 sherds are Chinese porcelain, which corresponds to 33.33% while 52 sherds were European ceramics, which corresponds to 66.66%. At the Convent São Domingos site, we recovered 16 sherds of Chinese porcelains, which corresponds to 8.88%, against 164 sherds of European ceramics, which corresponds to 91.11% of the total collection of imported ceramics. A list of the number of sherds found at each layer is given in Table 1.1 There were local, African-made ceramics found at either site, but the focus of this essay was only on imported ceramics. Based on comparative analysis, it was possible to establish a relative chronology of ceramics recovered at Abdurrazaque Juma’s house and Convent São Domingos.

The Convent of São Domingos is a small church with plain walls without any painting. It is often described as Manueline architecture due to its decorated walls with incised and relief lines and rectangular motifs. The interior and external face are undecorated, and it has two small rectangular windows and an arched door but both are very simple (Simbine 2021, 100).

As benchmark material, we relied upon the ceramics studied by Kirkman (1974) at Fort Jesus in Mombasa, Chittick (1974, 1984) in Kilwa Kisiwani and on Kilwa Island and Croucher (2006) in the clove plantations of Zanzibar. This comparison indicated that the chronological sequence of Abdurrazaque Juma house falls between the late seventeenth and early twentieth centuries CE, and the Convent São Domingos dates between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries CE.

| Abdurrazaque Juma’s house | Convent São Domingos | |||||

| Level (cm) | Chinese Porcelain | European Ceramics | Level (cm) | Chinese Porcelain | European Ceramics | |

| 0-10 | 0-10 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 10-20 | 5 | 7 | 10-20 | 2 | 10 | |

| 20-30 | 7 | 9 | 20-30 | 30 | ||

| 30-40 | 2 | 8 | 30-40 | 1 | 37 | |

| 40-50 | 4 | 8 | 40-50 | 3 | 19 | |

| 50-60 | 1 | 6 | 50-60 | 1 | 43 | |

| 60-70 | 2 | 4 | 60-70 | 3 | 2 | |

| 70-80 | 2 | 1 | 70-80 | 2 | 12 | |

| 80-90 | 2 | 1 | 80-90 | 1 | 2 | |

| 90-100 | 1 | 90-100 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 100-110 | 2 | 100-110 | 1 | |||

| 110–120 | 1 | 1 | 110-120 | 1 | ||

| 120-130 | 2 | 120-130 | ||||

| 130-140 | 1 | |||||

| 140-150 | 1 | Total | 16 | 164 | ||

| 160-170 | 2 | |||||

| 170-180 | ||||||

| 180-186 | ||||||

| Total | 26 | 52 | ||||

Interpretation

The excavation carried out in 2019 by the team of archaeologists from Eduardo Mondlane University on Mozambique Island unearthed evidence of imported goods that are material evidence of the region’s long participation in long-distance trade. The distribution of the finds aligns with our understanding of how Mozambique island and its urban society developed.

The island was the centre of exchange for diverse commodities, in particular ceramics, foodstuffs, wine, spices, and gold between Africans, Europeans, and Asians (Maritz 2020). Written sources such as Monografia da Ilha de Moçambique of 1944 and Navegação às Índias Orientais of 1897 identify Mozambique Island as a supplier of freshwater, foodstuff, and sailors, among other services for ships in transit towards long-distance voyages in exchange of goods from afar, in which the Chinese porcelains and European ceramics make the larger part. Furthermore, this island played a significant role in mediating the maritime networks, since ships that sailed in the Indian Ocean often passed through Mozambique Island to resupply, repair ships, wait for the monsoons, heal the sick, and shelter shipwrecked people.

Consequently, from the later seventeenth and early twentieth centuries CE, the participation in the long-distance trade network of the Ocean Indian and connections to the outside world created the social inequalities reflected by the existence of two different towns (fig. 2). The stone-town in the north side of the island came to be inhabited by those who came from Europe, and Portugal in particular, and controlled the political and economic power of the trading system. Their outward-facing world is exemplified in the architectural style of the city and the types of ceramics that they used and traded, which were largely from Europe. By contrast, the Macuti-town in the south side was occupied mostly by enslaved Makua people who could not trade without the Portuguese crown’s permission (Newit 2004). They inhabited wattle-and-daub architecture and sustained a separate urban sphere from those in the stone-town. It is worth noting that more Chinese porcelain was turned up in the site in Macuti-town. This may also relate to the chronology, as the Abdurrazaque Juma had an earlier occupation period than the Convent.

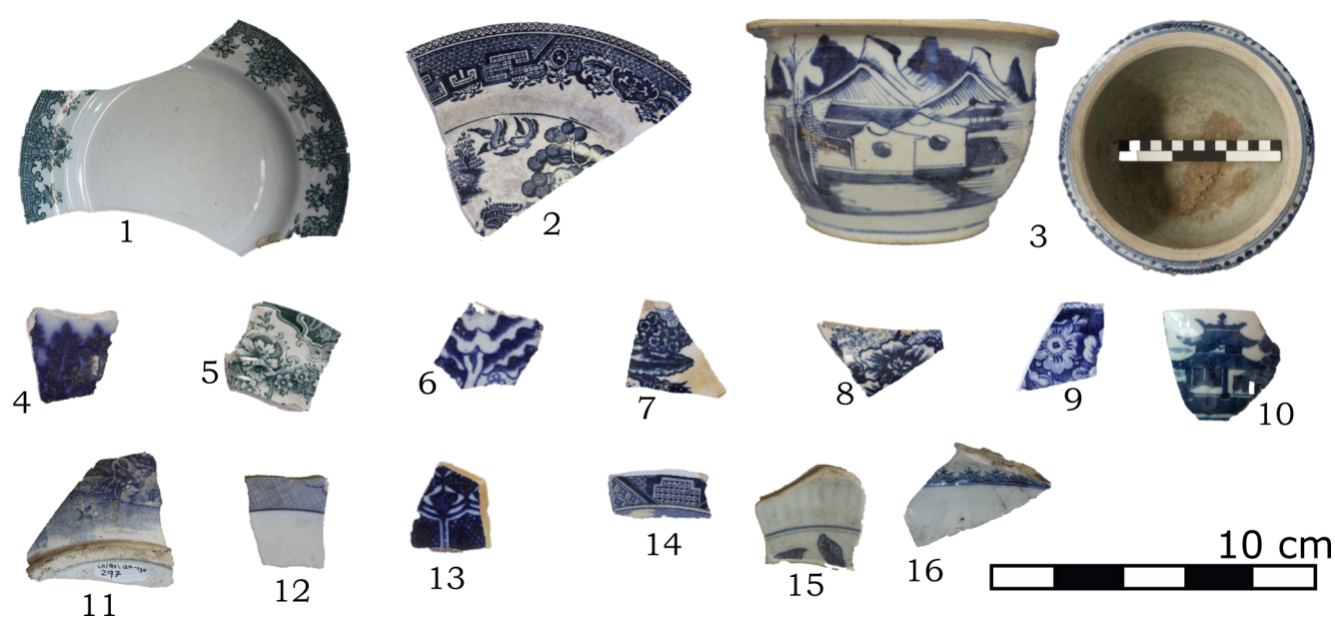

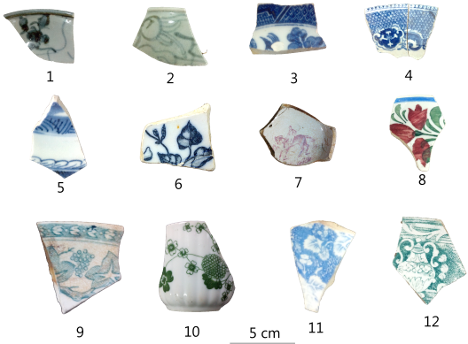

In general, our 2019 excavations found fewer Chinese porcelains on Mozambique Island compared to European ceramics. A small amount of diverse Chinese porcelain was found, but most were of European origin, namely blue transfer printed whiteware, flow blue willow pattern, blue, greyish, and green transfer-printed potsherds, mainly with the decoration of nature motifs similar to those excavated by Madiquida (2007) at Quissanga Beach and Foz do Lúrio. Of the smaller quantity of Chinese porcelain, we see blue and white wares with naturalistic decoration, which represented nature, landscapes, and palaces alongside undecorated fragments (fig. 3 and fig. 4). The minority categories of Chinese porcelain sherds recovered can be placed in the Early Qing period, dating to the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries CE and the late Qing period, eighteenth to twentieth centuries CE. In the same archaeological context of Convent São Domingos was also found a variety of European tin-glazed earthenware such as blue on white and blue and green on grey with a variety of decorative motifs and blue or green transfer-printed whiteware.

The chronological and geographical distribution of Chinese and European ceramics on Mozambique Island present key patterns within regional trade history. In the early phase of this trade, the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the most dominant ceramics seem to be Chinese porcelains, which are commonly associated with the global Sino-Swahili trade network2 (Rothman 2002; Klose 2007). In the later period, the importation of European ceramics became more common (Pendery 1999). This trade also involved the export of ivory, enslaved people, gold, timbers, pearls, seed pearls, ambergris, tortoise shells, animal skins and local potteries to Portugal and other western European countries and their northern American colonies (see Roque 1999; Beaujard 2007, 22).

Conclusion

To sum up, the occupation period at Abdurrazaque Jamu house and Convent São Domingos endured for about three centuries between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries CE. The statistical data revealed that blue and white Chinese porcelains of the Qing dynasty appeared in the minority at the excavations, perhaps because they were rarer and thus more expensive. A similar archaeological context was noticed at Sanje ya Kati and Songo Mnara where the low percentage of Chinese porcelain among other finds suggests the rarity and lack of access to Chinese porcelains. In addition, the decrease of Chinese porcelain can be attributed to the fact that from the late seventeenth century CE onwards, Europeans came to dominate transregional trading networks on Mozambique Island. The Muslim merchants that had traded Chinese porcelain in the Western Indian Ocean world for centuries were no longer dominating the trade. It appears that the consumption of ceramics turned toward the west and away from the east.

Therefore, the highest percentage of excavated ceramics belongs to European wares. We might presume that this is because they were considered to be cheaper foreign goods of easier access. Thus, they became a mainstay used by these households. These findings are significant because they add another dimension to the scholarship on the global trade of East Africa, which has long privileged a view toward the east, but has not explored these western connections so thoroughly.

Celso Simbine obtained his undergraduate degree at Eduardo Mondlane University (2011–2014), studying archaeological material collected in the inter-tidal areas for commercial and touristic purposes on Mozambique Island. He recently fulfilled his MS degree in Archaeology at the University of Cape Town (2019 – 2021), studying the chronological sequence of Mozambique Island. He is currently a PhD student at the University of Pretoria (2022-2025) , where he is researching Maritime Cultural Landscapes: A study of changing land use and coastal resource exploitation on Mozambique Island from AD 1000.

Simbine is a maritime and underwater archaeologist who has worked in coastal and underwater environments around Mozambique and the USA, in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. In 2015, he extended his interests in inter-tidal research on Mozambique Island when he became a collaborator of the Slave Wreck Project, participating in underwater and maritime environmental research using marine geophysics equipment to identify archaeological sites. He has also worked in the archaeological sites of Mozambique Island and Saint Croix to document or survey submerged sites. In addition, from 2023 and 2024, he participated in the preliminary excavations assessment of the IDM013 candidate to be a Slavery shipwreck, the L’Aurore sunk in Mozambique Island in AD 1789 with 600 slaves on board.

In February 2024, he participated in the Regional Training on Underwater Archaeology for the African Region in the scope of the project “Establishment of a Centre of Excellence for the Protection and Research of Underwater Cultural Heritage in Mozambique” that took place on Mozambique Island. Furthermore, he participated in the scientific dive training organized by UNESCO – CMAS in Turkey at Antalya–Kemer. He is responsible for the organization of the Maritime Archaeological Exhibition preparation on Mozambique Island to be placed at Fortress Sao Sebastião sponsored by Flanders-Belgica in collaboration with UNESCO-Maputo.

Read the next essay: “Simon and the kasuari” by Gitanjali Pyndiah >

- For analyses of characteristics and the origin of these ceramics (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4), the following references have been consulted Kirkman (1954, 1974), Chittick (1974, 1984), Sassoon (1981) Horton (1996), and Klose (2007). ↩︎

- At the time Swahili people of the East African Coast were traders on a global scale (Rothman 2002, 79). ↩︎

Reference List

Arkitektskolen I Aarhus, Danmark 1985. Ilha de Moçambique Relatório – Report 1982 – 85. Secretária do Estado da Cultura-Moçambique.

Beaujard, Philippe. 2019. “The Portuguese in the Indian Ocean.” In The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: A Global History, vol. II, 602-616. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chittick, Neville. 1974. Kilwa: An Islamic Trading City on the East African Coast. 2 vols. Nairobi: British Institute in Eastern Africa.

–––. 1984. Manda: Excavations at an Island Port on the Kenyan Coast. Nairobi: British Institute in Eastern Africa.

Croucher, Sara. 2006. “Plantations on Zanzibar: An Archaeological Approach to Complex Identities.” PhD diss., School of Arts, Histories and Cultures, The University of Manchester.

Duarte, Ricardo. 1993. “Northern Mozambique in the Swahili World, an Archaeological Approach. MPhil diss., Uppsala University.

–––. 2012. “Maritime history in Mozambique and East Africa: The urgent need for the proper study and preservation of endangered underwater cultural heritage.” Journal of Maritime Archaeology 7, no. 1 (October): 63-86.

Horton, Mark. 1996. Shanga: The Archaeology of a Muslim Trading Community on the Coast of East Africa. London: British Institute in Eastern Africa.

Klose, Jane. 2007. Identifying Ceramics. Historical Archaeology Research Group, Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town.

Kirkman, James. 1954. The Arab City of Gedi: Excavations at the Great Mosque, Architecture and Finds. London: Oxford University Press.

–––. 1974. Fort Jesus: A Portuguese Fortress on the East African Coast. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lobato, Alexandre. 1944. Ilha de Moçambique. Moçambique: Imprensa Nacional.

–––. 1953. Aspectos de Moçambique no Antigo regime colonial. Lisboa: Livraria Portugal.

Lopes, Teles. 1897. “Navegação às Índias Orientais.” In Colecção de Notícias para a História e Geografia das Nações Ultramarinas, vol. II. Lisboa: Academia Real das Ciências.

Madiquida, Hilário. 2007. “The Iron-Using Communities of the Cape Delgado Coast from AD 100.” MPhil diss., Uppsala University.

Madiquida, Hilário, and Joaquim Miguel. 2004. Rehabilitation of the Saint Sebastian’s Fortress Project Mozambique Island, Mozambique: Archaeological Excavations. Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo.

Maguire, Kristyn. 2007. “Analysis of Ceramics Recovered at Pinagbayanan, Juan Batangas.” MA thesis, University of the Philippines.

Maritz, Nicholas. 2020. “The Gold Hoard Aboard the Portuguese Ship Espadarte, Shipwrecked Around 1558.” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 75, no. 212 (June): 17–26.

Monclaros, Francisco. 1975. “Relação feita pelo padre Francisco de Monclaros, da Companhia de Jesus, da expedição ao Monomotapa, comandada por Francisco Barreto post.” In Documentos sobre os portugueses em Moçambique e na África Central 1497-1840, vol. VIII (1561-1588). Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos.

Mutiua, Chapane. 2014. “Ajami Literacy, ‘Class,’ and Portuguese Pre-colonial Administration in Northern Mozambique.” PhD diss., University of Cape Town.

Newitt, Malyn. 2004. “Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of an East African Coastal City, 1500-1700.” Portuguese Studies 20, no. 1 (January): 21–37.

Pendery, Steven. 1999. “Portuguese Tin-Glazed Earthenware in Seventeenth-Century New England: A Preliminary Study.”Historical Archaeology 33 (4): 58-77.

Pollard, Edward, Ricardo Duarte, and Yolanda Duarte. 2018. “Settlement and Trade from AD 500 to 1800 at Angoche, Mozambique.” The African Archaeological Review 35, no. 3 (September): 443-471.

Roque, Ana. 1999. “Da Ilha de Moçambique como porto de escala da Carreira da Índia, ou… Porque ao princípio era o mar e a ilha, Os Espaços de um Império–Estudos.” In Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, Lisboa, 47-59.

Rothman, Norman. 2002. “Indian Ocean Trading Links: The Swahili Experience.” Comparative Civilizations Review 46 (6): 79–90.

Sassoon, Hamo. 1981. “Ceramics from the Wreck of a Portuguese Ship at Mombasa.” Azania 16 (1): 97–130.

Simbine, Celso. 2020. “The Maritime Archaeology of Mozambique Island: Lessons from the Commercial Gathering of Beads and Porcelain for Tourists.” InMaritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Management on the Historic and Arabian Trade Routes, edited by Robert Parthesius and Jonathan Sharfman, 77-97. Cham: Springer.

–––. 2021. “An Assessment of an early 19th century AD Ceramic Assemblage from Mozambique Island.” MPhil diss., University of Cape Town.