Gitanjali Pyndiah

when the psychopathic winds that hauled

Africans out of address

have returned to song, to ocean, to verse like some

universe too far prolonged to cohabitate

— Canisia Lubrin, Voodoo Hypothesis

During the Indian Ocean Exchanges program, I started writing an essay based on my doctoral research which analysed the intersection between museum narratives and national history on Mauritius. I focused on the colonial representation and post-Independence imaginations of a national symbol, a ground-dwelling biped brought to extinction in the seventeenth century and canonised in the name of the dodo by Europeans. My aim is to write in a grammar and vocabulary that avoid reproducing the monstrous callousness of colonial depictions of the extinct biped.

In my review of scholarship about European slavery on Indian Ocean islands—including Mauritius, Rodrigues, Agaléga, Tromelin, St. Brandon Islands, the Chagos Archipelago, Réunion, and Seychelles—the encounter of a captive man, (re)named Simon, with the bird was a historical fragment that caught my attention.1 Nowhere in the imaginary of the biped, historically and in contemporary depictions, is the animal imagined from the eyes of the thousand men, women and children captured during the period of Dutch slavery and extractive colonisation in the region (1598-1710)

In the literature, Simon appears briefly as a twenty-five-year-old ‘black man’ who escaped his enslavers at the age of fourteen or fifteen and joined communities of maroons in the interior island of Mauritius. We know from the scholarship that a practice of subsistence livelihoods and organisation were already well defined in the inland forest 20 years before Simon would break from the terror of captivity. We find Simon in the colonial archive only because he is recaptured and is interrogated about the locations where he had lived for over a decade (1663 to 1674). From the testimony, transcribed by the enslaver, we are made to understand that Simon is spared punishment for promising to reveal the site of his dwelling. It is at this juncture that he mentions seeing the biped twice in the deep forest.

This encounter is also mentioned in some of the European literature on the bird’s extinction since the nineteenth century, as a side reference in the discussion about the speculative date of the last time when the animal was witnessed. Not only is Simon’s testimony dismissed and discredited, but a relationship with the live bird sharing the same refuge in the inland forests is never envisioned as a possibility. Part of my work is to re-imagine Simon in the absence of his and other captives’ existence in national museums on Mauritius. I draw from the contrast between the institutional silences around histories and stories of the enslaved and the hyper-visibility of the biped’s iconography and European narratives of extinction, often written ‘through the lens of a fetishized econostalgia’ (Ray, 2023). In the search for more such testimonies in the archive, I expand on those fragments and critically fabulate (Hartman, 2008) a narrative that museums and official historiographies have no capacity or intention of realising.

In November 2022, I received Simon’s original testimony while I was in Singapore on one of the international study trips during the program. This particular line is the focus of this short piece. ‘[Simon] also told us that, despite having been on the island for that long, he had seen a biped only twice, the bird being of the size of a casuaria’ (item 666). The reference to a ‘casuaria’, better known as cassowary — an English derivative of the Malay word ‘kasuari’, was intriguing. I had never heard of this bird previously. I found out that the kasuari was a ground-dwelling, tall biped with powerful legs and wide three-toed feet, like the extinct bird. The kasuari has a horn on the head, leathery black plumage, an iridescent bright blue neck, dagger-shaped claws and utters a rumbling which is among the lowest frequency sounds made by any bird. Today, the kasuari inhabit certain forests in Indonesia, on the Banda islands and in the highlands of Papua New Guinea for instance.

There was something potent about receiving this document while I was in Singapore and of all times the night before a scheduled visit to the National Museum of Singapore where an exhibition of bird illustrations from the Malay world was held, and two days before a trip to the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. Was I going to find exhibited a botanical drawing of a kasuari, a taxidermy mount, or a two-hundred-year-old skinned animal, in the absence of seeing and hearing the bird live? At the moment of reading the testimony, I wondered whether Simon could be from the Southeast Asia region. Names of captive men and women from Muluku, Batavia and Bali appear in the Indian Ocean colonial archives of slave resistance (Selvon, 2005).

Dress the animal in the field.

With your hands reach

into the thoracic cavity

and pull

the intestines,

— Rajiv Mohabir, The Taxidermist’s Cut

I start with the visit to the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum as a point of entry. The institution holds a nineteenth-century collection of more than half a million specimens, in the form of taxidermy mounts, skins of animals and other biotic materials from across the Indonesian/Malay/Pacific world (Onn, 2010). I was ready for a walk along rows of glass cabinets, cramped with taxidermy mounts of insects, butterflies, birds and bigger animals, from islands and lands once colonised by Europeans. A private tour in the vaults of the institution was also scheduled and I prepared myself for a guided visit of skyscrapers of temperature-regulated drawers holding thousands more sets of animal skins and fossilised and sub fossil organic matter.

It has been well documented that, apart from the highly seductive display of dinosaurs’ fossil bones and other big mammals, the ethnographic museum is built on bodies of animals, shot, skinned, stripped, stuffed and jarred under the extractive colonialism of the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, which would shape the natural sciences as a discipline. The display of inanimate animals — from taxidermy mounts to bodies and parts of bodies preserved in alcohol — as singular objects is a common feature of natural history museums (Haraway, 1989). It derives from a colonial logic of presenting the natural worlds and knowledges of places and people, colonised by the West, within a European system of taxonomic classification. The gruesome history of collecting specimens is usually never contextualised (Das and Lowe, 2018).

The Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum had created sensational exhibits for a psychedelic visitor experience. The wall in the lobby was covered with a hypnotic mandala made of repetitive photographs of skins of birds, butterflies, animal skulls, and transparent vials containing bodies and parts of bodies of lizards, fish and amphibians. Inside the museum, the jars of translucent bodies soaked in alcohol were also displayed against ultramarine, fuchsia and orange fluorescent lit cabinets to add to the dramatic effect.

Whenever I visit a natural history museum, it still surprises me how such institutions can sustain the aesthetisation of lifeless creatures as material culture and remain silent on the history of the extractive practices that allowed for such objects to be acquired. Are contemporary natural history curators grappling with how to rewrite narratives that do not fracture the lifeworlds, lores, beliefs and knowledges of the people those live animals have shared a habitat with for millennia? In post-Independence Mauritius, I observed a similar resistance to contextualising colonial collections. There, the Natural History Museum, for example, presents the biped as a nostalgic icon of extinction, without any reflection on colonisation and ecocide.

The history and culture of the vanquished and the oppressed is rarely embodied in material objects.

They bequeath words rather than palaces, hope rather than private property, words, texts and music

rather than monuments (Verges 2014).

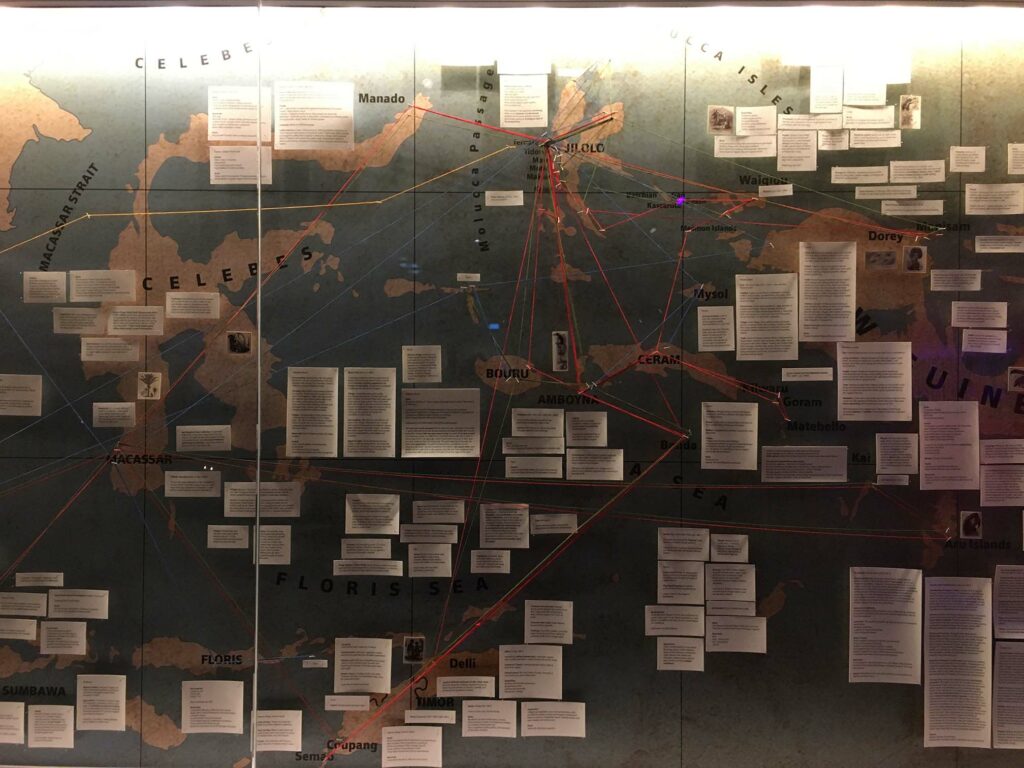

In my foraging for signs of a kasuari, I found a label which referred to the bird and other animals, pinned to a map of the Malay Archipelago showing the extensive colonial spread across islands where natural history specimens have been collected (fig. 1). There was no sign of a bird taxidermy anywhere. To my surprise, or not, an artistic model of an interpretation of the iconic biped from Mauritius was grandly displayed in a glass cabinet under an ambient violet light. Enclosed were also fossil bones, loaned by the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, another institution which prides itself for having a connection to the extinct bird, having acquired specimens as early as 1683 (Ray, 2023).

This model of the extinct biped is based on the recent shift in perspective, which rejects the long-held but erroneous representation of the bird as swollen. This exaggerated perspective is now refuted in some other museums, such as the Natural History Museum in London. However, I could not help imagining the life-size model of a kasuari, this majestic bird known for its capacity to defend itself ferociously if provoked, as the main feature of this immersive trance experience. This would at least have been contextually relevant. In the absence of finding this bird from the region in the museum space in Singapore, I enclose a picture of the kasuari here (fig. 2).

In the underground vaults of specimens, the visit was focused on showing the most radiant bird skins, in the typical preserved order: legs crossed over and held with tags. Stacks of corpses, with colourful feathers, laid on their backs with wings folded and beaks extended to fit in the drawer. An inanimate and inaudible version of a bird’s life, reminding us of the mass shooting that took place for the sake of collecting specimens. I found a label for the kasuari on a cabinet that the guide had not intended to open and insisted that he reveal its contents. A pale skin lay across the entire drawer, with a tag attached to its legs, the word ‘bought’ on it, reminding us of the transactional arithmetic of expendable life under colonisation (fig. 3).

Every memorial and museum to atrocity already contains its failure (Sharpe 2023, 38).

It struck me how the museum, in its exhibition space and storage vault, presented two lifeless specimens of the birds that were brought into conversation with each other through Simon‘s testimony. From my experience, the museum is a space of separation between life and the representation of living beings through objects. In the case here, it mediates between the dynamism of bird life–breathing, flying, rumbling, calling–and the display of inanimate skins and mounts, produced from the death of these respective animals and from their chemical recomposition and transformation. I left the institution and spent the evening immersed in the sonic geography of Papuan forests and human-animal interactions from documentary films and online videos. That allowed me to somehow imagine and visualise Simon in the ebony forest of the Indian Ocean island witnessing the biped in its once protective habitat.

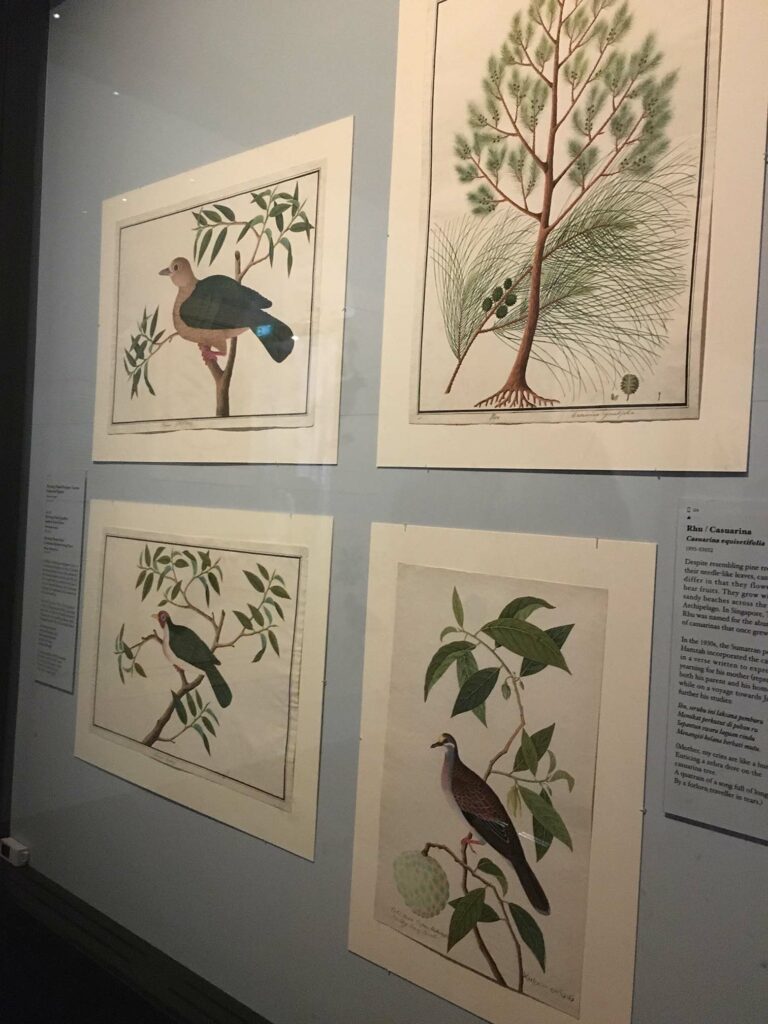

Two days earlier, an exhibition, A Voyage of Love and Longing at the National Museum of Singapore took us away from this monstrous capture of life to a ‘kind of reparation’ (Sharpe, 2023) that museums across the world are attempting to engage in today. Curated by Syafiqah Jaaffar, a scholar of Malay history and literature, the exhibition was inspired by the concept of Belayar, from a Malay term for the sea journey of coastal communities across the Indonesian archipelago.2 The curator was challenged to present a collection of nineteenth-century botanical drawings of Malayan plants and animals, commissioned during the same colonial period as the specimens in the natural history museum.

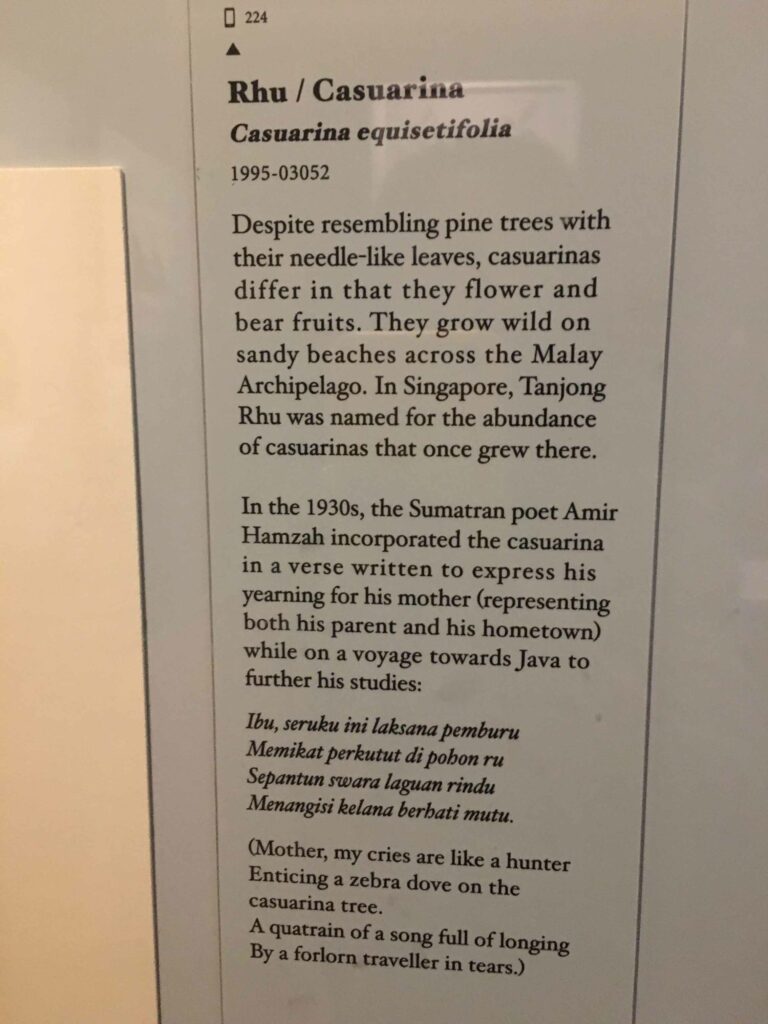

The illustrations were superimposed with narrative panels presenting lyrics from love ballads, classical texts and pantuns (rhyme quatrains) from Malay literature. The exhibition evoked a poetic and romanticised aspect of the voyage, in contrast with the extractive trope of discovery, and disrupted the taxonomic catalogue of illustrations by contextualising each plant and animal within a Malay geography and cosmology, and a pre-colonial genesis of naming. The exhibition shots (figs. 4 and 5) were chosen for their reference to the casuarina tree, a label that diverged from the Malay name rhu in order to adhere to European taxonomy, apparently because of the resemblance of its leaves to the kasuari’s feathers.

The narratives on the exhibit panels depicted everyday activities and emotions around the specific lifeforms, written with what I consider a methodological tenderness, an approach of reading and writing the nonmaterial culture of people and places subjected to colonial violence (physical and epistemological), with care and repair.3 The visit across the exhibition was facilitated by Jaaffar, whose intimate knowledge of the region—its pre-colonial history, literature, and everyday life—was shared with us with the same lyrical and poetic approach that the curation was conceived with.

The sea was their ‘‘lifeblood’’, binding them with other parts of the region for commercial, kinship and political purposes. A voyage was also a deeply transformative experience, signifying a physical and symbolic ‘‘break’’ from the comforts of home and the familiar, including loved ones (Introductory text panel, A Voyage of Love and Longing, National Museum of Singapore, 2023).

It made me think of the labour behind the work of repairing colonial narratives by tending to the erasure of lores and histories. The curator had to work within the limitations of the institutional archive and perform the emotional labour of educating a Singaporean public and visitors from abroad, who are often oblivious to the dynamics of power between the island and the Malay archipelago. A Voyage of Love and Longing was not necessarily a critique of the colonial enterprise of natural history but stood out as a carefully curated project illustrating how collections can be retrieved for interpretation within a museum context.

Although there were no drawings of a kasuari, which is understandable, as the bird is known for its distrust of man and could possibly not be captured on paper (or physically), the exhibition was a portal to this part of the world, possibly of Simon’s or other captives’ worlds before slavery, that I could immerse myself in tenderly.

Gitanjali Pyndiah is a UK-based Mauritian researcher and writer, with a PhD in Cultural Studies from Goldsmiths, University of London. She is a forthcoming Getty Scholar (2024/2025) under the Connecting Art Histories program, and an art history researcher in the Centre for Research on Slavery and Indenture at the University of Mauritius.

Gitanjali is working on her first monograph OūwKi the Unwinged Biped for dodo: outside monstrosity and taxonomy, based on her doctoral thesis. Her research interest lies in the visual-sonic history of the Kreol archipelagoes of the Indian Ocean (Mauritius, Réunion, Rodrigues, Chagos, Agalega, Tromelin and Seychelles). She has published several book chapters and articles.

Gitanjali also writes essays, fiction and poetry under the pen name Gitan Djeli. Her work appears in Mānoa A Pacific Journal of International Writing (forthcoming), The Funambulist, Doek!, adda, Poetry, Journal for the Study of Indentureship and its Legacies, among others. Her publications can be found at Gitanjali Pyndiah | The Getty – Academia.edu.

- A testimony recorded by the Dutch enslaver Hubert Hugo in a letter to the Cape Commander (South Africa) reporting the affairs of the colony — held in the Doyen Papers. ↩︎

- I thank Syafiqah Jaaffar for guiding us around the exhibition and the correspondence during the writing of this piece. ↩︎

- I draw from the influential work of Christina Sharpe, Professor of English literature and Black Studies, on an analytical and literary method of narration which tends to a grammar and vocabulary that do not reproduce the violence inherent in scholarship on slavery and colonisation. ↩︎

Reference List

“A Voyage of Love and Longing.” 2021. National History Museum Singapore. https://www.nhb.gov.sg/nationalmuseum/our-exhibitions/exhibition-list/a-voyage-of-love-and-longing.

Das, Subhadra, and Miranda Lowe. 2018. “Nature Read in Black and White: Decolonial Approaches to Interpreting Natural History Collections.” Journal of Natural Sciences Collections 6: 4-14.

Haraway, Donna. 1989. “Teddy Bear Patriarchy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908–1936.” In Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science, 26-59. London: Routledge.

Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe: A Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (June): 1-14.

Item 666, Hugo. H. Letter from Hugo to the Cape Commander, in the Doyen papers, Du XVIe au XIXe Siècle, un Aperçu de l’Histoire de Maurice, et Proceedings de la Société, CD-rom Royal Society of Arts & Sciences of Mauritius (RSAS): Réduit, Mauritius, 2013.

Lubrin, Canisia. 2017. “Long Wreckage.” In Voodoo Hypothesis, 77. Hamilton, ON: CBC Books.

Mohabir, Rajiv. 2016. The Taxidermist’s Cut. New York: Four Way Books.

Onn, Clement. 2010. “Learning Through Looking: The Natural History Collection of the Former Raffles Library and Museum.” BeMuse 3, no. 3 (July-September 2010).

Ray, Sugata. 2023. “Dead as a Dodo: Anthropocene Extinction in the Early Modern World.” TDR: The Drama Review 67, no. 1 (March): 126-135.

Selvon, Sydney. 2005. A Comprehensive History of Mauritius: From the Beginning to 2001. 2nd ed. Port-Louis: M.D.S.

Sharpe, Christina. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press.

–––. 2023. Ordinary notes. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Vergès, Françoise. 2014. “A Museum Without Objects.” In The Postcolonial Museum: The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History, edited by Iain Chambers, Alessandra De Angelis, Celeste Ianniciello, Mariangela Orabona, and Michaela Quadraro, 25-38. Surrey: Ashgate.