Dhaval Chauhan

Lamu was the final destination of our trip to Kenya, marking the culmination of the third and last leg of the Indian Ocean Exchanges Fellowship program. The town is situated on Lamu Island within the Lamu archipelago, approximately three hundred kilometers northeast of Mombasa along Kenya’s southeastern coast, overlooking the Indian Ocean. Historically, Lamu held a strategic position in transregional trade and migration networks, contributing to its development as a diverse and multifaceted society through frequent cultural contact with other mercantile-oriented societies in Africa and the western Indian Ocean.

Approaching Lamu is a sensorial experience. The white lime-washed facades of the waterfront gleam in the hot and humid air against the blue sky and ocean (fig. 1). As soon as I stepped into the shade from the sweltering sun, I felt a wave of calm and tranquility come over me. It is not surprising that this effect fascinated travelers who journeyed to this beautiful town over the centuries. The town is crisscrossed with narrow lanes, about two meters wide in most places. There is a cooling breeze in the lanes perpendicular to the waterfront, but the breeze dies down in the lanes parallel to the coast and one can feel the heat and humidity. These lanes are lined with stone houses which may be entered through porch-like spaces called the daka (figs. 2 and 3). The daka (plural madaka) is important in shaping the public life of houses in the Stone Town section of Lamu.

Based on a morphological reading of the daka in Lamu Stone Town, this essay argues that the daka serves not just as the physical entry point to the house but also plays a vital role in structuring the city’s public life. A close reading of the daka also challenges normative understandings of the stark division between private and public space.

The Lamu Stone House and the Daka

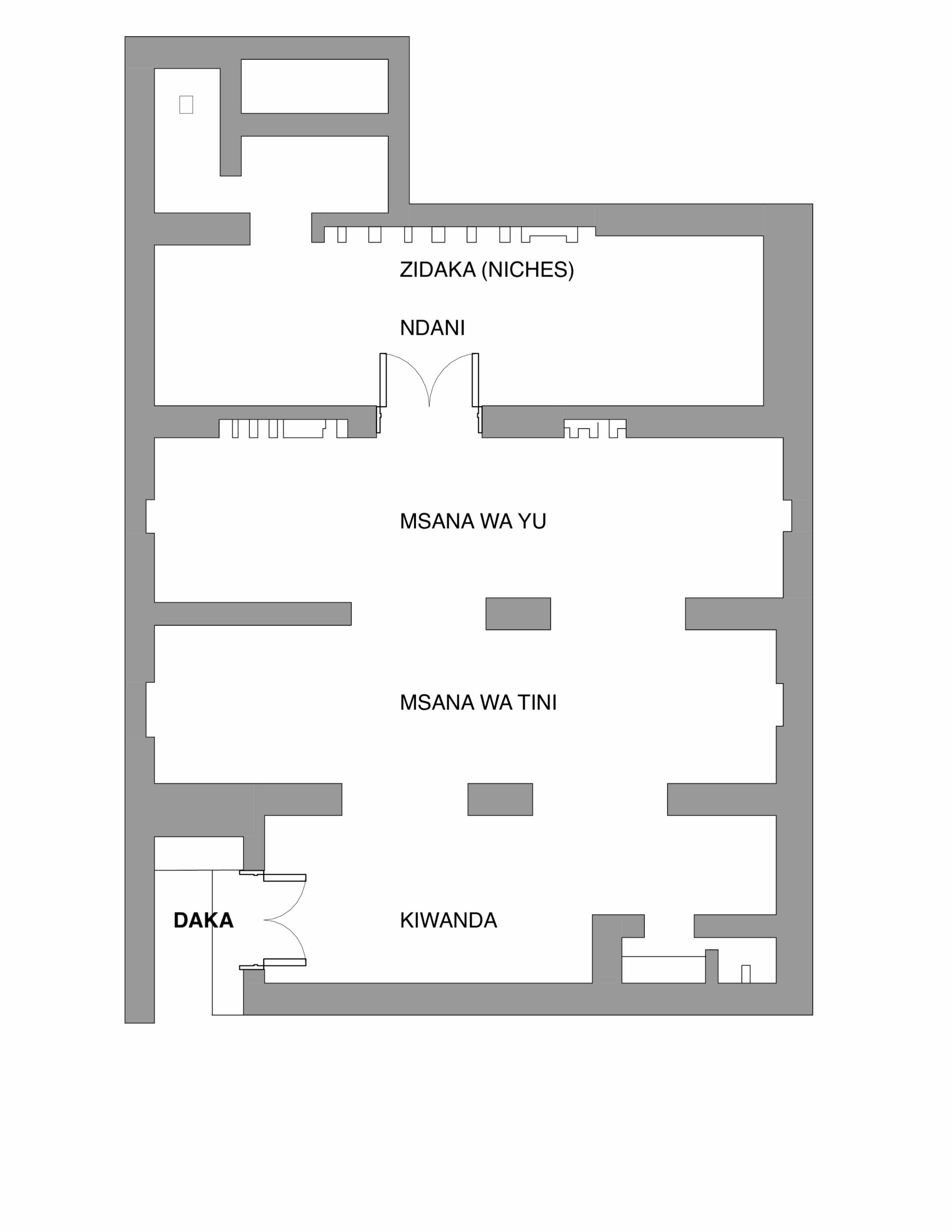

The stone houses on the Swahili coast are popular architectural features and have been objects of intense scholarly interest in diverse disciplines, including archeology, anthropology, and art history (Allen 1979, Donley-Reid 1990, Fleisher and Wynne-Jones 2012, Meier 2017, Wynne-Jones 2013). Most buildings along the waterfront, dating from the nineteenth century, are finished with limestone plaster and whitewashed, giving the town of Lamu a glistening appearance when one approaches it from the sea. The majority of the grand stone houses of Lamu Town date to the eighteenth century and belonged to local elite merchant and landowning families. They feature load bearing walls of coral limestone with mangrove wood beams supporting the floors and roof, and carved wood doors and windows. Typically, such multistoried houses have very small windows opening onto the streets which give them a fortified look. Each house is organized around a courtyard that brings in light and fresh air (fig. 4). The upper floors have terraces that allow for outdoor living and access to the ocean breeze.

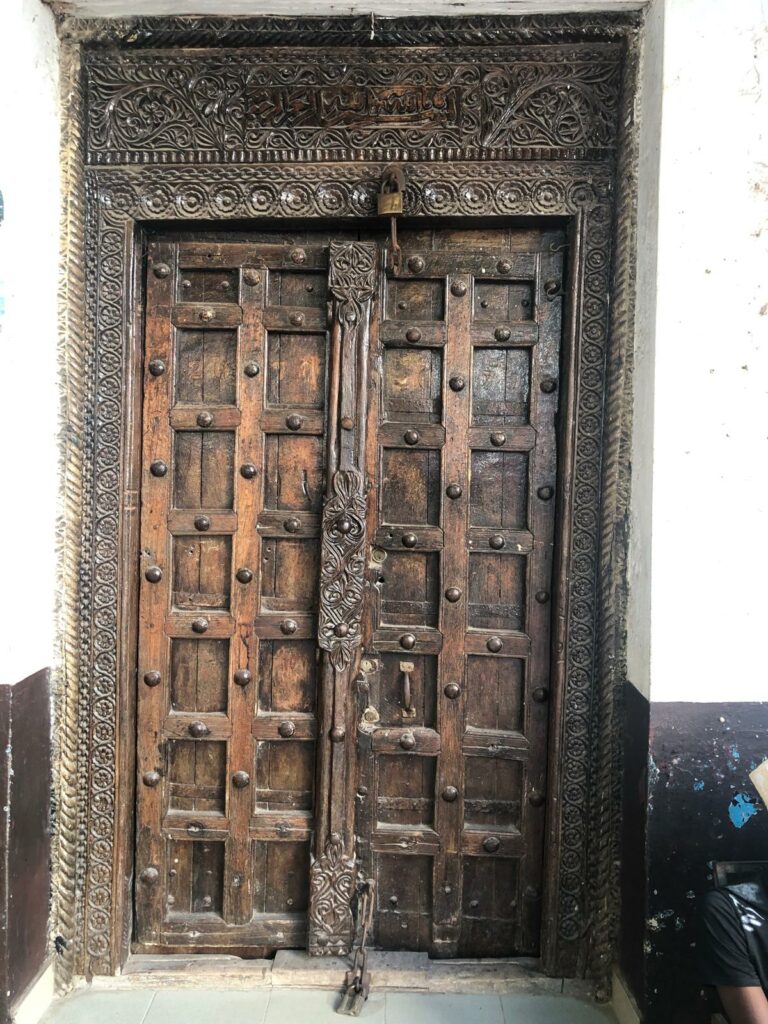

The exterior walls of the houses, which form a continuous façade along the street, are punctuated by the dark squarish daka that provide entry to each house. Typically, one side of the daka, perpendicular to the street, operates as the main entrance to the house. This entrance is the site of the famed Swahili carved doorways, which consist of double doors and ornate lintels and jambs (fig. 5). The other two sides provide inbuilt seating, locally called the baraza. The door then opens onto a squarish vestibule that leads into the rest of the house while the other two sides are blank walls (they might sometimes contain niches) (fig. 4). This spatial arrangement provides a transition from the street to the house, while making a clear distinction between the inside and outside. As an intermediary location, the baraza allows the daka to be treated as an outdoor space for social interactions. One can wait here until someone inside the house opens the door. Depending on the degree of familiarity, the owner may decide to invite the guest inside or they may conduct their conversation in the daka. The difference between the daka and a public space like a market square or the waterfront in Lamu is significant. The outdoor space of the daka allows for public social interactions but within a controlled environment. The space is attached to the house – one is still home – and is spatially also in the town. This dual positioning makes the daka a versatile architectural form.

The daka appears as if it is carved out of the solid mass of the stone walls. This effect is exaggerated as the daka’s surface is finished with a soft and fine lime plaster, similar to the interior of the house. In contrast, the exterior walls of stone mansions are often rough or not plastered. The daka’s refined finish and its beautifully carved wooden doors create a play of contrasts with the exterior’s rough limestone and coral-rag walls.

Vernacular residential architecture typically has porch-like spaces at entrances such as the verandah or patio which act as intermediaries between the spaces within the house and the outside. The daka is such an intermediary space but with some local specificities. It is the public face of the house, but once the main door is closed, unlike a porch or verandah, it is disconnected from the inside of the house. In contrast to the verandah, which belongs to the house and is controlled by its inhabitants, the daka does not allow any such control. It is a liminal space that forms a clear physical barrier between the interior of the house and the street while remaining accessible from the street. Further, the level of the daka and the street are almost the same, or minor enough not to form any barrier which allows the space of the street to flow easily into the daka. It is not and cannot be used in the same manner as a porch or verandah. Though the daka may be described as an intermediary space similar to the verandah, in its use and publicness, it is a unique spatial type.

A Versatile Public Space

Earlier studies of Swahili coast architecture paid much attention to the differentiation between public and private sections of the household, arguing that as one moves further from the entrance the spaces of the house become more private (Donley-Reid 1990). The concept of the intimacy gradient suggests the existence of distinct outer and inner worlds in Swahili coast societies. In contrast, the daka destabilizes such a rigid conception of public and private space. The inhabitants of the house can lay claim to it but cannot completely control it. On the one hand, morphologically, it is more open to the public domain of the city than it is to the house. On the other hand, it is a deep alcove, and the main door of the house opens onto it. The design and form of the daka suggest that it is an intrusion into the space of the house if the daka is occupied without consent. Therefore, though visible in the public arena and easily accessible from the street, it requires permission or an invitation to occupy it.

Viewed at the urban scale, the many madaka of Lamu Town create a constellation of public spaces that produce a public sphere that is also linked to the more private arena of each house. Each daka then acts as a small part of this larger sphere, which allows city inhabitants to participate in the public life of the town. The inhabitants of the individual houses have authority or control over their part of the public sphere through the daka. Thus, the daka defies any stark conceptual categorizations of public, semi-public, and private.

Due to its modest scale, the daka is a site of controlled sociality; due to its ubiquity, easy accessibility, and exposure to the street it is also deeply involved in the public life of the town. In this manner, it operates at different scales of interaction.

These preliminary observations on the daka and its function in the Lamu stone house suggest that this seemingly inconspicuous space is a pivotal feature in region’s urban landscape. The daka is a versatile mediator between the household and the town.

Dhaval Chauhan is an architect and academician whose research interests focus on the history of architecture and urbanism in India during the colonial and contemporary periods. By examining complex cultural exchanges, including overseas and maritime interactions, he aims to uncover the ‘subaltern’ agency of local actors that may have been overlooked in historical archives. His interests also include the architecture of the Indian Ocean region, architectural education, and the intersection of caste and architecture in India.

Dhaval is currently pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of California, Santa Barbara, as a recipient of the Regents Fellowship Award. He holds a Master of Architecture from the University of Texas at Austin, following his undergraduate studies at CEPT University in Ahmedabad, India. With over a decade of experience working as an architect in both India and the USA, he has undertaken residential, commercial, and industrial projects and continues to work on architectural design independently.

Since 2016, Dhaval has been teaching at art and architecture schools in India and the USA, covering subjects related to architectural design and the history of art and architecture. He has contributed to curriculum development at various stages of architectural education and was involved in the documentation of Ahmedabad’s old city, which was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Additionally, he has conducted surveys of vernacular and colonial-era housing across India.

Read the final essay: “Beneath the Surface: Travelling Coastal Kenya” by Vanessa Chen >

Reference List

Allen, James de Vere. 1979. “The Swahili House: Cultural and Ritual Concepts Underlying Its Plan and Structure.” In Swahili Houses and Tombs of the Coast of Kenya, edited by James de Vere Allen and Thomas H. Wilson, 1–32. London: Art and Archaeology Research Papers.

Baumanova, Monika, and Ladislav Smejda. 2018. “Space as Material Culture: Residential Stone Buildings on the Precolonial Swahili Coast in a Comparative Perspective.” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 73, no. 208 (December): 82–92.

Fleisher, Jeffrey, and Stephanie Wynne-Jones. 2012. “Finding Meaning in Ancient Swahili Spatial Practices.” African Archaeological Review 29, no. 2/3 (September): 171–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-012-9121-0.

Meier, Prita. 2018. “The Swahili House: A Historical Ethnography of Modernity.” In The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, 629–41. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Reid, Donley. 1990. “A Structuring Structure: The Swahili House.” In Domestic Architecture and the Use of Space, edited by Susan Kent, 114–26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vom Bruck, Gabriele. 1997. “A House Turned Inside Out.” Journal of Material Culture 2, no. 2 (July): 139–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/135918359700200201.

Wynne-Jones, Stephanie. 2013. “The Public Life of the Swahili Stonehouse, 14th–15th Centuries AD.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 32, no. 4 (December): 759–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2013.05.003.