Simone Struth, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

If I remain with those who follow not in my steps

It is more bitter than the dangers of the stormy sea.

Give me a ship and I will take it through danger,

For this is better than having friends who can be insincere.

At times I will accompany it through difficulties,

At others I will divert myself with society and late nights.

If there is no escape from society or from traveling

Or riding [the ship] then we have surely reached our final end.

This [ship] is a wonder of God, my mount, my escort.

In travel ’tis the house of God itself.1

Omani navigator Aḥmad ibn Mājid al-Saʿdī (Kitāb al-Fawāʾid fī uṣūl ʿilm al-baḥr wa-al-qawāʾid/ Book of Useful Information on the Principles and Rules of Navigation), written in 1489

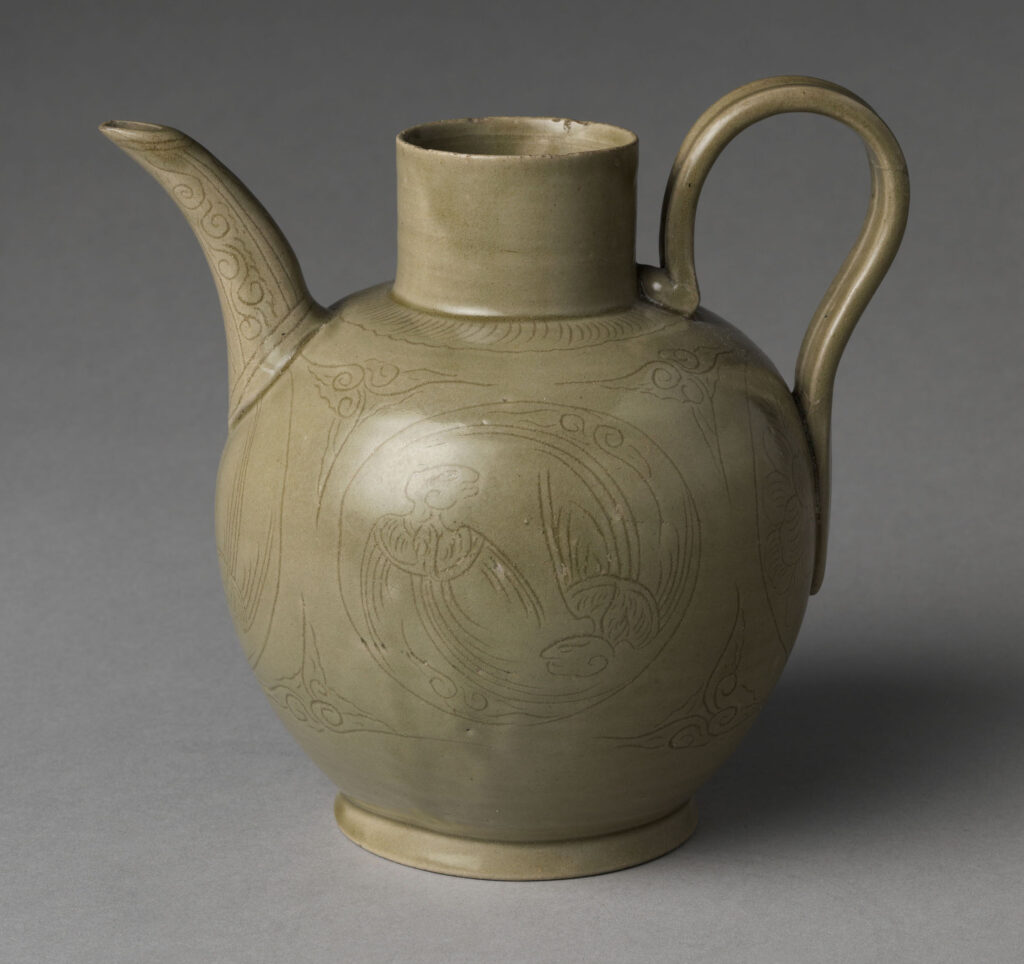

Sometime around 970, a merchant ship from Southeast Asia set sail on a voyage across the Java Sea, although its exact points of origin and destination are unknown. It likely loaded its first cargo on the coast of the South China Sea and headed southward via the Straits of Malacca with its major destination in the vicinity of today’s Sumatra and Malaysia, to the now-lost port of Srivijaya. Frequented as transhipment centres, these harbour cities and coastal sites served to transfer goods brought by ships sailing to and from West and East Asia, calling at ports in East Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. The ship must have stopped at one of these entrepôts, reloading the rest of its cargo with items of local producers or from the Gulf region, which then joined the goods already brought from present-day China. Laden with these precious goods, our boat sailed through Southeast Asian waters until disaster struck. Likely due to a cargo overload, the vessel sank in the northern Java Sea off the shore of Cirebon, a port city on the Indonesian island of Java. In 2003, local fishermen unexpectedly caught some Chinese ceramics in their nets, which once belonged to the cargo of this 10th century ship. For that reason, we refer to the shipwreck as the Cirebon Wreck (also known as the Nanhan Wreck).2 It rested at the bottom of the seabed until 2004, when the site underwent a complicated 18-month underwater excavation.3 Based on that excavation, we now know that the ship was of Malayo-Indonesian construction. It carried an array of goods with varied origins, from modern-day East Africa, the Gulf region, Iraq, Iran, western India, Sri Lanka, the Indonesian Archipelago, and China. During the course of the salvage, approximately 500,000 artefacts were retrieved, including ceramics, metalwork, glassware, rock crystal, gold jewellery, precious stones and pearls, ebony beads, tin and silver ingots, coins, and a wide collection of aromatic substances and spices. Thousands of rare ceramics from the Five Dynasties, known as Yue ware (also called “Green ware” or referred to more generically as celadon) were discovered. These predominantly green-glazed ewers, bowls, and plates were produced in Chinese kilns during the late ninth and the early tenth centuries, some of them decorated with parrot, dragon, butterfly, and lotus motifs (Liebner 2014, 6, 56–57, 83, 85).

Based on a small selection of Chinese Yue ware from the Cirebon Wreck – three ewers, one box and a dish (fig. 1) – this essay demonstrates the intertwined nature of distant and local maritime markets, using the example of the parrot to illustrate that not only objects but also living animals, ideas and artistic motifs circulated across cultures and dynasties throughout the Indian Ocean. While animate cargo was traded from Southeast Asia to East Asia, ceramics and other manufactured products decorated with related imagery were exported from imperial China back to Southeast Asia and on to the Gulf region and East Africa. The fascination with and representation of birds had a significant impact on culture, daily life, and art production in Tang and Song China as well as other parts of the Indian Ocean region in the pre-modern era, demonstrating the complex interconnectivity of the maritime exchanges.

Common to all five selected objects is their decoration. They feature a pair of parrots, incised or moulded on their surfaces. The expanded wings, their long tails that swoop below them and the shape of the beak characterise them as parrots. Intertwined and chasing after their tails, the two parrots form a circular motif that could be perfectly depicted on round boxes and dishes such as those from the shipwreck (fig. 2). These ceramics survived centuries of immersion in seawater and some were damaged by waves, salt and sand, which eroded their glazed surfaces (fig. 3).

Surely, the Cirebon ceramics are not the first instance of the parrot’s appearance in Chinese art. As a popular design, the parrot motif was already found on silver vessels (fig. 4) and bronze mirrors (fig. 5), as well as on objects crafted of other precious materials such as jade and mother-of-pearl (fig. 6) since the Tang dynasty. But parrots were not native to China, they came from Southeast Asia, by boat. While living animals and animal products had been traded from Southeast Asia to China since the first century, parrots in particular, turned into a popular and widespread artistic motif from the eighth century onwards. The so-called daoguaniao 倒掛鳥 (literally the “upside hanging down bird”), mentioned in several Chinese accounts from the Song and early Ming dynasty, was one of the most common parrot species in this region and might be the one depicted on the celadon vessels from the Cirebon shipwreck (Ptak 2012, 207–213). Su Shi (1037–1101), a famous writer during the Song dynasty, gave a description of some parrots in a poem, which were observed in a hanging position when resting on a tree. Describing them as “upside down hanging” winged creatures with “green feathers”, Su explains that these birds came from overseas (Shi 1998, 658–659, quoted after and translated into German by Röder 2009, 20). In later accounts from the Ming dynasty the daoguaniao was associated with Java and Borneo (Röder 2009, 24; Ptak 2012, 209). Imported from Southeast Asia to East Asia, these animals served as inspiration for artistic production as can be seen on the celadons.

For centuries, Yue ware was highly regarded by the imperial court in China before being exported and becoming fashionable not only in Japan and Korea, but also throughout the Indian Ocean region, mainly in South and Southeast Asia, but also in the Gulf region and as far as the east coast of Africa. Decorated with various motifs, these ceramics provide a compelling conjuncture of a far-reaching realm of shared taste and consumption that connected Asia with other empires across the Indian Ocean in pre-modern times.

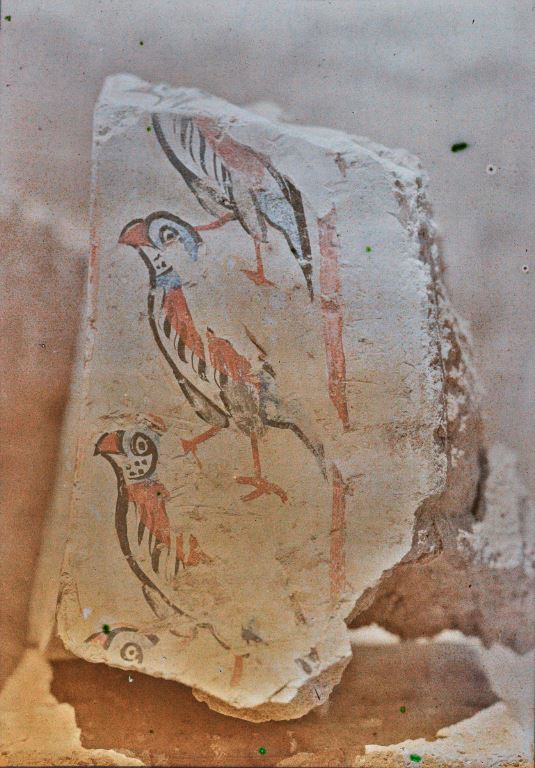

Some shards of Chinese celadons, for instance, were excavated in the Abbasid caliphal city of Samarra (modern-day Iraq) in the early twentieth century (fig. 7). While no representations of parrots have been found on the excavated shards in Samarra, we can confirm that the parrot did appear as an imported decorative motif, documented on some ninth-century wall paintings of Abbasid residences and palaces (fig. 8 and fig. 9). The Yue ceramic finds from the Cirebon shipwreck provide a convincing example of Chinese export ceramics that were likely destined for the Gulf region. When paired with the evidenced circulation of popular live cargo, we can extend the possibility that the decorated green objects from the Cirebon Wreck may have been destined for a city like Samarra.

Moving beyond material culture, parrots are also found in medieval and early modern Arab and Indo-Persian literature. They appeared mainly in adventurous stories as talking parrots alongside other characters such as travellers and merchants. The epistle The Case of the Animals versus Man before the King of the Jinn written by a group of scholars in Basra known as the Ikhwān al-Ṣafā (commonly translated as the “Brethren of Purity”) in the 960s, revolves around seventy men who are shipwrecked in the island Sāʿun which is inhabited by talking animals, one of which is a parrot (al-babghāʾ) (Goodman and McGregor 2012). Another popular work dating back to the 14th century is the Tuti-Nama (“Tales of the Parrot,” fig. 10). Originally written in Sanskrit in the 12th century, it was known as the Śukasaptati (“Seventy Tales of the Parrot”). Consisting of adventure stories narrated by a domestic parrot to his mistress Khojasta night after night – similar to Scheherazade in A Thousand and One Nights – the parrot tries to prevent Khojasta from leaving the house to meet her lover while her merchant husband is travelling (Almutawa 2015).

The Middle Eastern fascination with birds and avian products from Southeast Asia continued beyond the Abbasid period into later empires as well. In the 13th century, a cockatoo was traded to Cairo from the northern tip of Australia, Indonesia, or the islands of New Guinea. According to the manuscript De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (“The Art of Hunting with Birds”), written in the 1240s and held in the Vatican Library, this cockatoo was sent to Sicily as a gift by the Ayyubid Sultan al-Kāmil (r. 1218–1238) to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220–1250) (Dalton et al. 2018, 36, 45–49). The exchange of living creatures, and birds in particular, continued for several hundred years and in addition to parrots and cockatoos the birds of paradise, which were native to New Guinea and some neighbouring islands, were traded largely by Dutch merchants to Europe in the 17th century. Highly valued for their exquisite plumage, these birds, which came to Europe as diplomatic gifts, became aesthetically and politically charged exotica, attracting naturalists, aristocrats, and artists alike (Swan 2015, 621).

The Indian Ocean circulation of birds and avian products, and the parrot more precisely, demonstrates the complex geographical, socio-cultural, and economic connections and trade dynamics of the Indian Ocean. Indeed, the fascination with birds became a longue durée phenomena reflected in the continuous trade of parrots and other animals from Southeast Asia across Middle Eastern cultures and dynasties. Along with other goods traded by sea or recovered within shipwrecks, the small selection of Chinese Yue ware from the Cirebon Wreck offers a rare glimpse into the world of seafarers, bearing witness to the complex interconnectivity and entangled histories of Indian Ocean exchanges and the dynamic nature of the cargo that they carried. These five objects, brought up from the floor of the Java Sea after residing there for over 1000 years, also help us to better understand the shared investments and preoccupations of medieval artisans from Abbasid Iraq and Tang China, reflecting the taste of the elite at the time.

Simone Struth is a curator at the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar. She is responsible for the Online Collection and the new permanent galleries dedicated to the Indian Ocean trade and the spread of Islam to China and Southeast Asia. An art historian by training, she studied Islamic Art History, Byzantine Art History and Modern German Literary Studies at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich and in Cairo. From 2013 to 2015, she worked as a research associate for the Samarra-Project MOSYS 3D at the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin. Specialized in Abbasid art, she completed her PhD thesis on the Abbasid stucco material from Samarra, funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation. Since 2018, she has been part of the curatorial team in Doha, working on several projects, including the re-installation of the museum’s permanent galleries and the temporary exhibition Baghdad – Eye’s Delight (2022/2023). Simone is the author of several articles such as ‘Sailing the Indian Ocean: Sea of Sailors and Merchants’ (2022), ‘And the Eyes Gaze, Roaming in a Brilliant Place: Behind the Walls of Abbasid Palaces’ (2022), and ‘Herzfeld’s theories reconsidered. An interdisciplinary method for a new reading of the Abbasid stucco panels from Samarra’ (2020). Her research interests center on transfer movements, trans-culturalism and Abbasid art in global perspectives and trade and cultural exchange across the Indian Ocean. She is also interested in Southeast Asian textiles and jewellery from the 19th century as well as modern and contemporary art with a focus on Egypt and Iraq.

simone.struth@gmail.com

- Aḥmad ibn Mājid al-Saʿdī, Kitāb al-Fawāʾid fī uṣūl ʿilm al–baḥr wa–al-qawāʾid, 1489. Quoted after Edward Alpers, The Indian Ocean in World History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 3–4. ↩︎

- The wreck-site was reported to the Indonesian salvage company PT Paradigma Putra Sejahtera (“The National Committee for Salvage and Utilisation of Valuable Objects belonging to the Cargoes of Sunken Ships”), which applied for survey and salvage licenses. Licensed by PanNas BMKT to commence operation in April 2004, a Belgium-led team of Cosmix Underwater Research and Recovery Ltd. in partnership with PT Paradigma Putra Sejahtera began to salvage the wreck. See Horst Hubertus Liebner, “The Siren of Cirebon: A Tenth-Century Trading Vessel Lost in the Java Sea” (PhD diss., The University of Leeds, School of Modern Languages and Cultures, East Asian Studies, 2014), 14-15, 17. ↩︎

- As part of the initial regulations to sell retrieved objects, PANNAS BMKT sold the artefacts of the wreck on behalf of the Government of the Republic of Indonesia in 2010 through the Office of National Property Claims and Auctions (KPKNL) Jakarta III; later versions, however, increasingly emphasised the role of items of national cultural heritage that are to be excluded from commercial exploitation. Since 2010, a revised law on cultural heritage states that cultural heritage is classified as present “on land and/ or in water.” See Liebner, “The Siren of Cirebon,” 14–15, 17. ↩︎

Reference List

Almutawa, Shatha. 2015. “A 17th-Century Indian Parrot: Interpreting the Art of the Deccan.” Perspectives on History. The Newsmagazine of the American Historical Association, July 1, 2015. https://www.historians.org/research-and-publications/perspectives-on-history/summer-2015/a-17th-century-indian-parrot.

Alpers, Edward. 2014. The Indian Ocean in World History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dalton, Heather, Jukka Salo, Pekka Niemelä, and Simo Örmä. 2018. “Frederick II of Hohenstaufen’s Australasian Cockatoo: Symbol of Detente between East and West and Evidence of the Ayyubids’ Global Reach.” Parergon 35 (1): 35–60. https://DOI:10.1353/pgn.2018.0002.

Dongfang, Qi. 2010. “Gold and Silver Wares on the Belitung Shipwreck.” In Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsson Winds, ed. by Regina Krahl, John Guy, J. Keith Wilson and Julian Raby, 221–227. Washington D.C. and Singapore: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, National Heritage Board of Singapore and Singapore Tourism Board.

George, Alain. 2015. “Direct Sea Trade Between Early Islamic Iraq and Tang China: From the Exchange of Goods to the Transmission of Ideas.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 24, no. 4 (October): 1–46.

Goodman, Lenn E., and Richard McGregor, eds. 2012. The Case of the Animals versus Man before the King of the Jinn: A Translation from the Epistles of the Brethren of Purity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Guy, John. 2019. “Shipwrecks in Late First Millennium Southeast Asia: Southern China’s Maritime Trade and the Emerging Role of Arab Merchants in Indian Ocean Exchange.” In Early Global Interconnectivity across the Indian Ocean World, Volume 1: Commercial Structures and Exchanges. Palgrave Series in Indian Ocean World Studies. Edited by Angela Schottenhammer, 121–163. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Liebner, Horst Hubertus. 2014. “The Siren of Cirebon: A Tenth-Century Trading Vessel Lost in the Java Sea.” PhD diss., The University of Leeds, School of Modern Languages and Cultures, East Asian Studies.

Mājid al-Saʿdī, Aḥmad ibn. 1489. Kitāb al-Fawāʾid fī uṣūl ʿilm al–baḥr wa–al-qawāʾid.

Ptak, Roderich. 2012. “Chinese Bird Imports from Maritime Southeast Asia, c. 1000–1500.” Archipel: études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien 84: 197–245. https://DOI:10.3406/arch.2012.4371.

Röder, Mathias. 2009. “Vom kopfüber Hängenden oder daoguaniao.” In Tiere im alten China: Studien zur Kulturgeschichte. Vol. 20, Maritime Asia, edited by Roderich Ptak, 17–30. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Shi, Su. 1998. Dongpo ci biannian jianzheng 東坡詞編年箋證. Xi’an: San Qin chubanshe.

Swan, Claudia. 2015. “Exotica on the Move: Birds of Paradise in Early Modern Holland.” Art History 38, no. 4 (September): 620–635. https://DOI:10.1111/1467-8365.12171.

Zhao, Bing. 2015. “Chinese-style Ceramics in East Africa from the 9th to the 16th Century: A Case of Changing Value and Symbols in the Multi-Partner Global Trade.” Afriques. Débats, méthodes et terrains d’histoire 6. https:// DOI:10.4000/afriques.1836